The formal consistency of Petra & Paul Kahlfeldt Architekten’s facades for a mixed-use development in Munich pays tribute to the city’s tradition of very large buildings

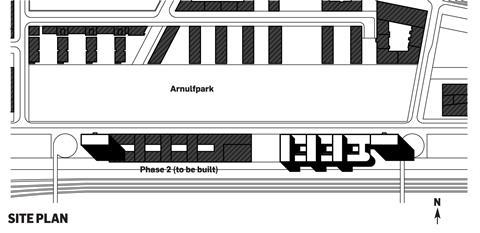

A large urban block has recently been completed on the site of a former railway depot near the centre of Munich. One side faces a vast railway landscape, while the other stretches along the Arnulfpark, a 40,000sq m park around which a new residential district is fast emerging. The scheme is based on a winning competition entry by three practices, Petra & Paul Kahlfeldt Architekten, Ekert & Probst Architekten and Frank & Probst Architekten.

住宅建在Arnulfpark的对面,由垂直于公园的线性板块组成。通过采用多种建筑表达方式,这种安排的形式纯粹性被显著软化。即使该方案采用了一种更一致的语言,但这种安排——街区之间公共空间的流动分布——是否足以证明是对广阔的铁路景观的有力回应,仍然是一个疑问。然而,已经建立起来的东西读起来就像一篇新现代主义缓和的文章,每一个细节都被区分开来,以至于整体被剥夺了力量。失败不仅仅是品味的问题。未能认识到该项目的城市意义,未能以适当的规模投资。

In determined opposition to the expression of this earlier housing, the Kahlfeldt team’s project comprises two closed perimeter blocks of a highly consistent architectural language. Their formal manipulation is complex.

A continuous three-storey mass defines each block’s perimeter, while three seven-storey slabs subdivide them — the one subtle acknowledgement of the housing on the other side of the park.

A pair of 13-storey towers book-end the new ensemble. The proposal seemingly orders the site in a single 450m-long gesture.

The group effort was directed not to differentiation but integration of expertise

The team divided design responsibility so that each practice might best contribute its own expertise while maintaining a unified expression. The Kahlfeldts designed the facades, Ekert & Probst planned the residential tower while Frank & Probst planned the offices. During the implementation phase it was decided that the office of Arno Lederer would design the second block (still waiting to start on site) while respecting the typological and formal decisions of the Kahlfeldt scheme. Again, the group effort was directed not toward differentiation, but to the integration of different expertise.

保罗·卡尔菲尔德热情地列出了该计划的参考资料。首先,慕尼黑有建造非常大的建筑的悠久传统,通常包括整个城市街区——利奥·冯·克伦泽的作品提供了一些这种现象的例子。但还有更多最近的消息来源也在发挥作用。kahfeldt提到了他的老师和前校长Josef Paul Kleihues的工作和Oswald Mathias Ungers的城市理论。昂格斯关于“巨形”(德语为Grossform)的观点尤其切题。在20世纪70年代,昂格斯得出结论,尽管保持城市的连贯性是可取的,但它不再是一个现实的目标。在他看来,现代城市所能提供的最好的东西,是不同城市实体的蒙太奇,每一个都有明显的规模和独特的身份。

Ungers reintroduced to the architectural discourse a rich history of large forms that provide internal consistency at the scale of the building while contributing to the definition of public spaces and a larger urban order. Some examples — such as von Klenze’s work — appear rich and timeless. Others appear diagrammatic and have yet to earn their place in history — some of Ungers’ own buildings come to mind.

While Ungers and Kleihues were regarded as opposing intellectual forces in the Berlin of the late 20th century, Paul Kahlfeldt readily admits his indebtedness to both. Kleihues’ interest in the crafting of building and the critical reconstruction of historic cities provided the fertile soil for Berlin’s architectural revival after reunification in 1989. The rhetoric of the city’s chief planner, Hans Stimmann, moved freely between a concern for urban form and the crafting of architecture.

The design might be likened to a dance, a complex series of moves small and large

In one interview he put it simply. “When one only stays within the typological realm, everything is simultaneously right and wrong. And many houses look like that. It does make an enormous difference whether a door handle is made of plastic, bronze or stainless steel.”

Stimmann的柏林提供了无数欧洲大师工作的实验室,Kollhoff & Timmermann和kahfeldt Architekten等当地事务所也从这里诞生。这些建筑师将老一辈的冲突抛诸脑后。概念和工艺融合为建筑实践,寻求参与世界的商业项目开发。

The megaform that the Kahlfeldt team has realised at Arnulfpark illustrates this attitude perfectly. Built for a real-estate investment company, it is a true hybrid building, designed without concern for the expression of individual functions. The lower parts are commercial spaces while the two tower blocks have a complicated residential programme. The size and layout of the apartments varies almost from floor to floor. There are very small studios, but also enormous penthouses that occupy an entire floor. Very little of this programmatic variety is made visible.

The entire development is clad with Portuguese limestone and is based on an almost uniform grid, which extends unabated into the inner courts. Where the grid is varied it is in the interests of architectural idiosyncrasy rather than functional expression. The ground-floor facades are treated as a plinth, punctuated by doors expressed as if they were the entrances to a big house. The upper-floor windows of the apartment towers appear as a cornice.

The three north-south oriented slab blocks employ deeper window reveals than the rest of the building and a bay width that is half that used elsewhere. That more insistent rhythm is extended down into the plinth, introducing a minor disruption to the long facades. The higher and heavier parts of the building dominate — the consequence of a self-evident formal logic.

At this point we might revisit the earlier observation that the building organises the site in one gesture. Rather than adopting a singular graceful move, in the Zaha Hadid sense, the design might be better likened to a dance — a complex series of moves, small and large, evoking human emotion while pursuing a highly considered choreography.

Introducing a recent lecture in Rotterdam, Paul Kahlfeldt showed an image of a stone column within a brick-lined space and stated that he had just two friends: the pillar and the brick. The complexity of the one-liner was lost on his audience of Dutch architects. Was this poor man a lonely soul? As suggested above, the Kahlfeldts are not without friends at all. And they have each other. Petra and Paul Kahlfeldt interrogate each other’s work both in the office and at the kitchen table.

Strangely, one can take Kahlfeldt’s joke literally while still having to think twice. A pillar is a pillar, a brick is a brick — but

they are more than just the prime tectonic manifestations of a load-bearing structure. Kahlfeldt said pillar and not column, and he said brick not wall. Columns and walls have tectonic meanings, but also manifest themselves in particular forms that carry cultural meanings.

最终,正是这种人文主义为我们提供了慕尼黑项目的经验。我们欣赏石雕的工艺,以及其比例塑造的经典形象;我们认为这座建筑是我们已经熟悉的建筑家族的一部分。这些不是城市的标志,不是标志性的建筑,而是大城市里的大房子。

The bias in current architecture is towards the picturesque, not just in the traditionalist realm but in modernism too. The Kahlfeldts’ sensibility is closer to that of a figure like John Nash. Although he certainly had a talent for the picturesque, Nash is best known as the author of large-scale interventions in London. Around 1800 he constructed an urban masterpiece that stretched from St James’s Park to Regent’s Park. The conventional terrace was the typological point of departure. The architectural ordering of the facades was conceived by Nash and prescribed to architects who did the odd interiors of individual dwellings. Top-down urbanism did not exist as we know it today. Nash’s classicism now looks familiar, but it was tough and radical once. In the same sense Arnulfpark is a radical project.

Postscript

Hans van der Heijden is design director of Biq Stadsontwerp, Rotterdam

8Readers' comments